Das Orbital Widget Toolkit

von Florian Blasius, mit der Unterstützung der Rust Gemeinschaft

Kommentierung und Dokumentation durch Ralf Zerres und alle Unterstützer

Diese Version des Textes geht davon aus, dass Du OrbTk v0.3.1 oder

nachfolgend in Verbindung mit einer Rust Toolchain v1.41 oder

nachfolgend verwendest. Cargo.toml sollte in den Metadaten

edition="2018" definieren. Dies ermöglicht die Nutzung von Rust 2018

Edition spezifischen Konstrukten in allen abgeleiteten Projekten.

Vgl. “Installations” Abschnitt in Kapitel 1 um OrbTk zu installieren oder zu aktualisieren.

The 2020 Edition diese Buchs ist das erste erstelle Release. Es wird zusammen mit der OrbTk version 0.3.1 veröffentlicht.

- Appendix A, “Keywords,” erläutert neu eingeführte Bezeichner.

- Appendix D ist ein stetig fortschreitender Arbeitsprogress. Neue Freigaben diese Buches erfolgen nach deren Fertigstellung. Ebenso wie deren Übersetzung in unterstützte Sprachvarianten.

Um dieses Buch online zu lesen wird eine HTML gerenderte Version unter

OrbTk-Book (de) veröffentlicht. Alternativ kann es

auch für die Offline-Nutzung auf lokal installiert werden. Entweder

wird dazu eine gerenderte pdf oder ebook Version heruntergeladen.

Oder das Buch wird aus dem Quellcode erzeugt. Das Rendern erfolgt mit dem Aufruf von

mdbook build --dest-dir doc/book_de

Vorwort

Diese Buch spricht alle Rust Entwickler an, die moderne, schnelle und erweiterbare Benutzeroberflächen erstellen wollen. Da alle Komponenten von OrbTk in Rust selbst kodiert sind, erbt es alle Vorteile ihrer herausragenden Infrastruktur. Der minimalistische Ressourcenverbrauch, die Speichersicherheit und ein komprimierter, gut strukturierter, modularer Quellcode sind Schlüsselfaktoren, die OrbTk zu einer vielversprechenden Basis für Deine zukünftigen Multiplattform-GUI-Projekte machen.

Bereits in den 80er Jahren waren Laufzeitumgebungen wie Java Vorreiter für die Idee einer “Einmal programmieren, überall laufen lassen”-Werkzeugkette. Rust in Kombination mit OrbTk bietet die Möglichkeit, dieses Ziel zu verwirklichen und gleichzeitig Geschwindigkeit, Sicherheit und Multithreading im Blick zu behalten. Es steht Dir frei, die Möglichkeiten moderner Hardware zu nutzen: Reize die Vorteile von Multicore-CPUs in Mikrocomputern, Einplatinencomputern oder der Vielfalt von Cloud-Infrastrukturen aus. Mit Rust kannst Du nativen Binärcode kompilieren. OrbTk bietet die benötigten Crates, um GUIs zu produzieren, die den Anforderungen der Benutzer entspricht: schnell, sichere, zuverlässig und Plattform übergreifend!

Du wirst dich an einer freundlichen Community und verständlichen Texten erfreuen. Du wirst nicht nur Deine Kenntnisse in der GUI-Entwicklung erweitern, sondern auch Dein Verständnis von Rust-Code verbessern. Tauchen ein und mache Dich bereit ein Mitglied der OrbTk- und Rust-Gemeinschaft zu werden!

— Ralf Zerres

Einführung

Willkommen zu Das Orbital Widget Toolkit, einem Einführungsbuch über

OrbTk. Die Programmiersprache Rust hilft Dir, schnellere und

zuverlässige Software zu schreiben. OrbTk bringt die nötigen

Komponenten mit, um moderne grafische Benutzeroberflächen zu

entwickeln. Es bietet eine kohärente Codebasis, die zu nativem

Binärcode kompiliert wird, welcher auf der gewünschten Zielplattform

ausgeführt wird.

Merkmale

- Moderne, leichtgewichtige API

- Plattformübergreifend

- Modulare Komponenten.

- Basiert auf der Entity-Component-System-Bibliothek DCES

- Flexibles Ereignissystem

- Integrierte Widget-Bibliothek

- Benutzerdefinierte Widgets

- Benutzerdefinierte Theming-Engine

- Dynamische Themenumschaltung

- Integrierte Debugging-Werkzeuge

- Lokalisierung

Unterstützte Plattformen

- Redox OS (nativ)

- Linux (nativ | cargo-node)

- macOS (nativ | cargo-node)

- Windows (nativ | cargo-node)

- openBSD (nicht getestet, sollte aber funktionieren)

- Web (cargo-node)

- Android (nativ geplant | cargo-node)

- iOS (nativ geplant | cargo-node geplant)

- Ubuntu Touch (nativ geplant | cargo-node geplant)

Für wen OrbTk gedacht ist

OrbTk ist ideal für Programmierer, die die Vorteile der

Programmiersprache Rust nutzen wollen. Es besteht keine

Notwendigkeit, Datenstrukturen und Typen zu transformieren: OrbTk

selbst ist in Rust geschrieben. Es übernimmt somit natürlich alle

strukturellen Vorteile der Programmiersprache und stellt die

benötigten GUI Elemente bereit, um Deine grafische Anwendung zu

programmieren. Schauen wir uns ein paar der wichtigsten Gruppen an.

Teams von Entwicklern

Rust erweist sich als produktives Werkzeug für die Zusammenarbeit in großen Teams von Entwicklern mit unterschiedlichem Kenntnisstand in der Systemprogrammierung. Wirf auch einen Blick in das Rust-Buch, welches die grundlegenden Prinzipien erläutert, und dir hilft besseren und sicheren Code zu produzieren.

OrbTk verwendet die Rust-Toolchain so weit wie möglich wieder.

Zeitgenössische Entwickler, die die Lernkurve durchlaufen haben, werden deren Vorteile nutzen:

- Cargo, der mitgelieferte Abhängigkeitsmanager und das Build-Tool, macht das Hinzufügen, Kompilieren und Verwalten von Abhängigkeiten mühelos und konsistent im gesamten Rust Ökosystem.

- Rustfmt sorgt für einen konsistenten Formatierungsstil unter den Entwicklern.

- Der Rust Language Server unterstützt die integrierte Entwicklungsumgebung (IDE) ihrer Wahl was Integration für Code-Vervollständigung und Inline-Fehlermeldungen betrifft. Natürlich vorausgesetzt, dass die IDE ihrer Wahl das LSP und die Sprache als solches unterstützt.

Studenten

Rust ist für Studenten und alle, die sich für das Erlernen von Systemkonzepten interessieren. Mit Hilfe von Rust haben viele Leute etwas über Themen wie Betriebssystementwicklung gelernt. Die Community ist sehr einladend und beantwortet gerne Fragen von Anfängern und Studierenden. Durch Bemühungen wie dieses Buch, will das Rust-Team die Systemkonzepte von Rust mehr Menschen zugänglich machen. Insbesondere solchen, die neu in der Programmierung sind.

Unternehmen

Hunderte von Unternehmen, große und kleine, verwenden Rust produktiv für eine Vielzahl von Aufgaben. Zu diesen Aufgaben gehören Kommandozeilen-Tools, Web-Services, DevOps-Tooling, eingebettete Geräte, Audio- und Videoanalyse und Transkodierung, Kryptowährungen, Bioinformatik, Suchmaschinen, Anwendungen für das Internet der Dinge, oder maschinelles Lernen. Sogar große Teile des Firefox-Webbrowsers sind mittlerweile in Rust neu geschrieben worden.

Open-Source-Entwickler

OrbTk ist für Leute, die mit der Programmiersprache Rust, zusammen

mit der Gemeinschaft, ihren Entwickler-Tools und Bibliotheken arbeiten

wollen. Wir würden uns freuen, wenn Du zum Ökosystem mit seinen

Komponenten und Einträgen beitragen könntest. Du bist herzlich

eingeladen.

Für wen ist dieses Buch?

Dieses Buch setzt voraus, dass Du bereits Code in einer anderen Programmiersprache und anderen GUI-Toolkits geschrieben hast. Es ist nicht wesentlich, welche Sprache oder welches Toolkit dies war. Wir haben versucht, das Material so aufzubereiten, dass Personen mit einer Vielzahl von Entwicklungshintergründen damit arbeiten können. Im Fokus liegt nicht ein Diskurs was Programmierung ist oder wie man darüber denkt. Wenn Du völlig neu in der Programmierung bist, wäre es besser, wenn Du zunächstein Buch zur Hand nimmst, das speziell die Einführung in die Programmierung zum Thema hat. Auch hier gibt es von der Rust-Gemeinschaft bereits einige Anstrengungen, wie z.B. Rust By Example.

Wie man dieses Buch benutzt

Im Allgemeinen geht dieses Buch davon aus, dass Du es in der Reihenfolge von vorne nach hinten liest. Spätere Kapitel bauen auf Konzepten früherer Kapitel auf, und frühere Kapitel gehen möglicherweise nicht mehr im Detail auf ein bereits besprochenes Themas ein; Ist es wesentlich, greifen wir das Thema typischerweise in einem späteren Kapitel wieder auf.

In diesem Buch finden Sie zwei Arten von Kapiteln: Konzeptkapitel und Projektkapitel.

In Konzeptkapiteln lernst Du einen Aspekt von OrbTk kennen. In

Projektkapiteln werden wir gemeinsam kleine Programme schreiben und

dabei das bisher Gelernte anwenden.

Kapitel 1 erklärt, wie man Rust und OrbTk installiert, wie man ein

minimales Programm schreibt und wie Du cargo, den Paketmanager und

das Build-Tool von Rust, verwendest.

Schließlich enthalten einige Anhänge noch nützliche Informationen über Rust in einem eher referenzähnlichen Format.

- Anhang A behandelt die Schlüsselwörter von OrbTk

- Anhang B behandelt OrbTks ableitbare Merkmale (traits) und Komponenten (crates).

Es gibt keinen falschen Weg, dieses Buch zu lesen: Wenn Du vorwärts springen willst, nur zu! Du musst vielleicht zu früheren Kapiteln zurückspringen, wenn ein späteres Kapitel dich verwirrt. Was immer für Dich funktioniert ist richtig.

Ein wichtiger Teil des Lernprozesses von OrbTk ist das Lesen der

Fehlermeldungen, die der Compiler anzeigt: Diese helfen Dir

funktionierenden Code zu erstellen oder diesen zu verbessern. Daher

werden wir auch Beispiele haben, die sich nicht kompilieren lassen.

Zusammen mit der Fehlermeldung, die der Compiler bereitstellt können

dann die Ursachen erklärt und eine funktionierende Lösung erarbeitet

werden.

Beachte bitte, dass Deine Eingaben um ein beliebiges Beispiel auszuführen, möglicherweise nicht sofort kompiliert! Stelle dann bitte sicher, dass Du auch den umliegenden Text zum Beispielcode mit einbeziehst. Ferris hilft sicher auch, den Code zu erkennen, der nicht funktionsfähig ist:

| Ferris | Bedeutung |

|---|---|

| Dieser Code lässt sich nicht kompilieren! | |

| Dieser Code ist panisch und verweigert die Zusammenarbeit! | |

| Dieser Quellcode enthält unsicheren Code. | |

| Dieser Code erzeugt nicht das gewünschte Verhalten. |

In den meisten Situationen führen wir Dich anschliessend zur korrigierten Version des Codes, der dann kompiliert werden kann.

Quellcode

Die Quelldateien, aus denen dieses Buch generiert wurde, findest Du auf der Homepage unter Orbtk book (de).

Erste Schritte

Beginnen wir mit Deiner OrbTk-Reise! Es gibt viel zu erlernen, fangen wir einfach mal anfangen. In diesem Kapitel werden wir folgendes erörtern:

- Die Installation von OrbTk auf Linux, BSD, macOS und Windows.

- Das Schreiben einer OrbTk-Anwendung, welche ein Fenster darstellt und in dessen Mitte

Hallo OrbTk!erscheint. - Die Benutzung von

cargo, Rusts Abhängigkeiten- und Komponentenmanager und auch Build-System.

Installation

Der erste Schritt, ist die Installation von Rust. Dies wird im Folgenden link Rust-Buch Kapitel 1 ausführlich beschrieben.

Wenn wir eine OrbTk-Anwendung erstellen, definieren wir die benötigten Abhängigkeiten zu den OrbTk-Komponenten (crates) in der Datei Cargo.toml unseres Projekts. Der Kompiliervorgang löst die Referenzen auf und lädt den Quellcode nach Bedarf herunter.

Kommandozeilen-Notation

In diesem Kapitel und im gesamten Buch werden wir einige Befehle zeigen, die im Terminalfenster erscheinen. Zeilen, die Du in einem Terminalfenster eingeben solltest, beginnen alle mit

$. Du brauchst das Zeichen “$” nicht einzugeben; es visualisiert einfach den Beginn jedes Befehls. Zeilen, die nicht mit “$” beginnen, zeigen normalerweise die Ausgabe des vorherigen Befehls. Außerdem wird in PowerShell-spezifischen Beispielen “>” anstelle “$” verwendet.

Fehlersuche

WIP: Auflistung der häufigsten Schuldigen und Bereitstellung einiger grundlegender Lösungen.

Lokale Dokumentation

OrbTk bietet die Möglichkeit, die Dokumentation lokal zu installieren, so dass Sie sie offline lesen können.

Immer, wenn ein Typ, eine Funktion, eine Methode oder eine Komponente (crate) vom Toolkit referenziert wird und Du Dir nicht sicher bist, was dieser bzw. diese tut, oder wie er bzw. es zu verwenden ist, werfe einen Blick auf die Dokumentation der Programmierschnittstelle (API) um es herauszufinden!

Hallo OrbTk!

Nachdem du nun die erforderlichen Bausteine installiert hast, lass uns

dein erstes OrbTk Programm schreiben. Es Tradition mit der

Einarbeitung in eine neue Programmiersprache ein kleines Programm zu

schreiben, das die Worte Hello, world! auf den Bildschirm ausgibt.

Also los. Wir erstellen eine minimale App, die ein Fenster erzeugt und

dieses Fenster an den gegebenen Koordinaten auf dem Bildschirm positioniert.

Das Widget wird unsern Text zentrieren.

Anmerkung: Diese Buch geht davon aus, dass du Basis-Kenntnisse bei der Bedienung der Kommandozeile besitzt. Rust selbst hat keine speziellen Anforderungen, welche Werkzeuge du für das editieren von Quellcode verwendest und wo du diesen abspeicherst. Wenn du also bereits mit einer integrierten Entwicklungsumgebung arbeitest (IDE), nur zu, es spricht nichts dagegen diese auch für OrbTk zu nutzen. Viele IDEs besitzen mittlerweile ein gewisses Maß an Unterstützung für die Sprache Rust. Prüfe einfach die vorhandene Dokumentation. In letzter Zeit hat das Rust Team ein besonderes Augenmerk auf die Integration von IDE Unterstützung gelegt. Und es wurden große Fortschritte in dieser Richtung erzielt!

Ein Projekt-Verzeichnis erstellen

Zunächst wird eine Verzeichnis erstellt, in dem wir unseren OrbTk Quellcode speichern wollen. Es spielt für rust und OrbTk keine große Rolle, wo sich dieser befindet. Aber für die Beispiele und Übungen in diesem Buch solltest Du einen Unterordner projects in deinem Home-Verzeichnis erzeugen. Wir werden im Folgenden immer auf diesen referenzieren.

Öffne ein Terminal und tippe die folgenden Kommandos ein um die gewünschte Unterordner Struktur projects zu erzeugen:

Für Linux, BSD, macOS und Power-Shell unter Windows:

$ mkdir -p ~/orbtk-book/projects

$ cd ~/orbtk/projects

In der Windows Shell:

> mkdir "%USERPROFILE%\orbtk-book"

> cd /d "%USERPROFILE%\orbtk-book"

> mkdir projects

> cd projects

Erstellen und starten der OrbTk Applikation

Im nächsten Schritt erzeugen wir ein neues Projekt und verwenden hierzu Cargo. Mit einer .toml Datei beschreiben wir die für den Rust Code erforderlichen Abhängigkeiten und Metadaten. Das stellt sicher, das auch bei Folgeaufrufen der Kompilier-Prozesses (build) eine konsistentes Ergebnis erzeugen kann.

Tippe einfach ein:

$ cargo new orbtk_hello

$ cd orbtk_hello

Das erste Kommando, cargo new, verwendet als erstes Argument den Projektnamen.

(“orbtk_hello”). Das zwiete commando wechselt in das neu erstellte Projekt Unterverzeichnis.

Schauen wir uns das erzeugte Cargo.toml mal an:

Filename: Cargo.toml

[package]

name = "orbtk_hello_example"

version = "0.1.0"

authors = ["Your Name <you@example.com>"]

edition = "2018"

# See more keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

[dependencies]

Listing 1-1: Default Metadaten “orbtk_hello”

Mit cargo new, wurde die Projekt Struktur automatisch

erstellt. Vielleicht wurden auch schon die Angaben für Autor und Email angepasst,

wenn Cargo diese Metadaten aus deinen Umgebungsvariablen auslesen konnte.

Cargo hat auch bereits den Quellcode für “Hello, world!” erzeugt.

Lass uns die in der Quelldatei src/main.rs prüfen:

Filename: src/main.rs

fn main() { println!("Hello, world!"); }

Listing 1-2: Default source file “main.rs”

Es gibt keinen Grund, diesen Stand unseres Programmes mit cargo run zu kompilieren,

da wir zunächst noch ein paar Projekt Metadaten zusammen mit ein paar Code Zeilen ergänzen wollen.

Aktualisierung von Cargo.toml

Zuerst öffne bitte die Cargo.toml Datei und gib die Code-Zeilen aus dem Listing 1-1 ein:

Filename: Cargo.toml

[package]

name = "orbtk_hello"

version = "0.3.1-alpha4"

authors = [

"Florian Blasius <flovanpt@posteo.de>",

"Ralf Zerres <ralf.zerres.de@gmail.com>",

]

description = "The Orbital Widget Toolkit - Training project"

documentation = "https://docs.rs/orbtk"

repository = "https://github.com/redox-os/orbtk"

readme = "README.md"

license = "MIT"

keywords = [

"orbital",

"widget",

"ui",

]

edition = "2018"

[profile.dev]

opt-level = 1

[dependencies]

orbtk = { git = "https://github.com/redox-os/orbtk.git", branch = "develop" }

#orbtk = { path = "../../../orbtk", branch="next" }

[[bin]]

name = "orbtk_hello"

path = "src/main.rs"

Listing 1-1: Project metadata “orbtk_hello”

Vielleicht wundert es Dich, warum die Eigenschaft name in der Cargo.toml Datei

als hello_orbtk formatiert wurde.

name = "orbtk_hello"

Es ist eine sinnvolle und empfehlenswerte Gewohnheit, den Rust

Namenkonventionen zu folgen. Ich möchte dich ermutigen, in Rust Code

sogenannte snake_case Namen zu nutzen. Wenn wir unsere OrbTk

Beispiele erweitern, werden wir den Gruppierungsprefix orbtk weiter

verwenden. Aus diesem Grund verwenden wir für unser erstes kleines

Programm den Namen orbtk_hello.

Aktualisierung von main.rs

Der gesamte OrbTk spezifische Quellcode der für die Übersetzung des ersten Beispeilprogramms “Hello OrbTk!” notwendig ist wird in Listing 1-2 angezeigt. Diesen bitte in die Datei src/main.rs übertragen.

Filename: src/main.rs

use orbtk::prelude::*;

fn main() {

// use this only if you want to run it as web application.

orbtk::initialize();

Application::new()

.window(|ctx| {

Window::new()

.title("OrbTk-Book - Chapter 1.2")

.position((100.0, 100.0))

.size(420.0, 140.0)

.child(

TextBlock::new()

.font_size(28)

.h_align("center")

.text("Hey OrbTk!")

.v_align("center")

.build(ctx)

)

.build(ctx)

})

.run();

}

Listing 1-2: Quellcode zum erzeugen des Fensters und Ausgabe von “Hey OrbTk!”

Speicher die Datei und gehe zurück in dein Terminal Fenster. Gebe die folgenden Kommandos ein um das Programm zu Kompilieren und zu starten:

$ cargo run --release orbtk_hello

Anmerkung: Eventuell ist die Installation der Entwicklungsversion von SDL2 über den Paketmanager der Distribution erforderlich (Ubuntu: libsdl2-dev).

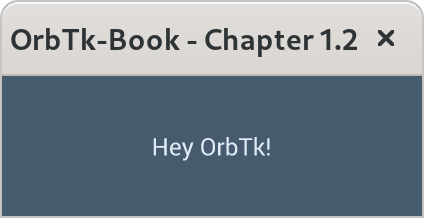

Gleichgültig welches Betriebssystem du gerade verwendest, ein Fenster

sollte sich auf dem Bildschirm öffnen, das dein Text Hey OrbTk!

zentriert in diesem Fenster ausgibt.

Image 1-2: Applikations-Fenster mit Hey OrbTk

Wenn etwas die Fensterausgabe verhindert, schau bitte im Abschnitt “Troubleshooting” der Installationsbeschreibung nach, um Hilfestellungen zu erhalten.

Wenn die die gerenderte Ausgaben von Hey OrbTk! deiner App bewundern kannst,

Glückwunsch! Du hast erfolgreich deiner erste OrbTk Anwendung geschrieben.

Das macht Dich zum OrbTk Programmierer — willkommen!

Anatomie einer OrbTk Anwendung

Lass uns die Details ansehen, was gerade mit dem Aufwurf der “Hey OrbTk!” Anwendung passiert ist. Hier kommt das erste Puzzel-Teilchen:

Für den Moment sollte es ausreichen, die ersten Puzzleteile zu entzaubern. Wenn Du einen generischen Blick auf die Struktur werfen willst, in Abschnitt Workspace besprechen wir weitere Details.

use orbtk::prelude::*;

fn main() {

// use this only if you want to run it as web application.

orbtk::initialize();

Application::new()

.window(|ctx| {

Window::new()

.title("OrbTk-Book - Chapter 1.2")

.position((100.0, 100.0))

.size(420.0, 140.0)

.child(

TextBlock::new()

.font_size(28)

.h_align("center")

.text("Hey OrbTk!")

.v_align("center")

.build(ctx)

)

.build(ctx)

})

.run();

}

Die erste Zeile fügt die use Anweisung ein. Eine use Anweisung wird verwendet, um den Pfadname abzukürzen der notwendig ist, um in Rust einen Modul zu referenzieren. Die Anweisung prelude ist ein bequemer Weg eine Liste von Dingen zusammenzufassen, die Rust automatisch in dein Programm importiert. In unserem Fall haben wir den Pfad orbtk::prelude eingebunden. Alle Elemente die über diesen Pfad addressiert werden können (in der Notation mit :: beschrieben) können jetzt als Kurzform über ihren Namen angesprochen werden. Es ist nicht mehr nötig hierzu den expliziten Pfadname mit zu erfassen (orbtk::prelude::)

use orbtk::prelude::*;

fn main() {

// use this only if you want to run it as web application.

orbtk::initialize();

Application::new()

.window(|ctx| {

Window::new()

.title("OrbTk-Book - Chapter 1.2")

.position((100.0, 100.0))

.size(420.0, 140.0)

.child(

TextBlock::new()

.font_size(28)

.h_align("center")

.text("Hey OrbTk!")

.v_align("center")

.build(ctx)

)

.build(ctx)

})

.run();

}

Die dritte Zeile definiert eine Rust Funktion. Der Funktionsname

main ist insoweit besonders, als das immer die Stelle in einem Rust

Programm angibt, mit der die Code-Ausführung beginnt. In unserem Fall

hat main eine Parameter und liefert auch am Ende der Funktions

nichts zurück. Gäbe es Parameter, sie stünden innerhalb der Klammern, ().

Bitte beachte ebenso, dass die Funktion-Körper (body) in gescheiften

Klammern eingebettet ist, {}. Die Rust Syntax erwartet dies für alle

Funktionsdefinitionen. Im Rust Code-Style ist es üblich, die

Geschweifte Klammer auf der gleichen Zeile wie die

Funktions-Deklaration zu plazieren und dazwischen ein Leerzeichen einzgeben.

Rust bedient sich eines Tools für die automatische Formatierung von

Codezeilen: rustfmt. Es hilt Dir, am Rust Code-Style innerhalb

deiner Projekte konsistent zu bleiben. OrbTk folgt dieser Anleitung.

Abhängig von der Versionsnummer deiner installierten Rust Toolchain

ist die Programmversion von rustfmt vermutlich schon auf deinem System

installiert. Andernfalls prüfe bitte die Online-Dokumentation.

Innerhalb der main Funktion findest die die folgenden Anweisungen:

use orbtk::prelude::*;

fn main() {

// use this only if you want to run it as web application.

orbtk::initialize();

Application::new()

.window(|ctx| {

Window::new()

.title("OrbTk-Book - Chapter 1.2")

.position((100.0, 100.0))

.size(420.0, 140.0)

.child(

TextBlock::new()

.font_size(28)

.h_align("center")

.text("Hey OrbTk!")

.v_align("center")

.build(ctx)

)

.build(ctx)

})

.run();

}

Hier gibt es einige wichtige Details herauszustellen.

- Erstens, Rust code wird standardmäßig mit vier Leerzeichen eingerückt, keine Tabulatoren!

- Zweitens, die Methode

orbkt::initializevollzieht alle notwendigen Schritte, um das OrbTk Umgebung zu initialisieren.

use orbtk::prelude::*;

fn main() {

// use this only if you want to run it as web application.

orbtk::initialize();

Application::new()

.window(|ctx| {

Window::new()

.title("OrbTk-Book - Chapter 1.2")

.position((100.0, 100.0))

.size(420.0, 140.0)

.child(

TextBlock::new()

.font_size(28)

.h_align("center")

.text("Hey OrbTk!")

.v_align("center")

.build(ctx)

)

.build(ctx)

})

.run();

}

- Drittens, die Methode

Application::newerstellt eine neue Entität im verwendeten Entity-Component-System (DECS). DECS ist eine OrbTk Abhängigkeit die die Erstellung und die Organisation aller innerhalb von OrbTk verwendeten Entitäten verwaltet. die OrbTk Methoden verändern die Attribute der Widget Elemente, die entsprechenden DECS Objekte speichern diese Attribute als Compenenten der gegebenen Entity.

Wir werden die OrbTk Makros und Methoden detaillierter in Kapitel

<WIp: chapter> besprechen. Im Moment genügt das Wissen, dass mit dem

Aufruf von ::new() die Methode zur Erstellung eines neuen Widgets

angesprochen wird (hier: Application)

Nun zur den nächsten Zeilen:

use orbtk::prelude::*;

fn main() {

// use this only if you want to run it as web application.

orbtk::initialize();

Application::new()

.window(|ctx| {

Window::new()

.title("OrbTk-Book - Chapter 1.2")

.position((100.0, 100.0))

.size(420.0, 140.0)

.child(

TextBlock::new()

.font_size(28)

.h_align("center")

.text("Hey OrbTk!")

.v_align("center")

.build(ctx)

)

.build(ctx)

})

.run();

}

Innerhalb der Application Methode, starten wir weitere

Anweisungen. Das Augenmerk liegt auf folgenden Details:

- Erstens, das Rust Stylingsystem rückt den Code um weitere vier Leerzeichen ein. Keine Tabulatoren!

- Zweitens, das

Pipeliningvon Code wird über einen Punkt (dot) eingeleitet, der um den neuen Methodennamen ergänzt wird (Hier:window). - Drittens, die

windowsMethode verwendet eine Rustclosureals Argument.

Wenn du bis jetzt noch nicht mit dem Konzept von closures vertraut

bist, dieser Link ist den Freund:

closures.

Diese Referenz bietet ein vertiefendes Verständnis. Im Moment genügt

das Wissen, dass eine closure als effiziente Sprachkomponente an

Stelle einer Funktion genutzt werden kann, Wenn eine closure |ctx| {} ausgeführt wird, wird deren Ergebnis innerhalb der

Rückgabevariable gespeichert (hier: ctx). Die Geschweifte Klammer

definiert den closure Korpus, mit dem Quellcode der innerhalb der closure ausgeführt wird.

Lass und den closure Korpus mal prüfen:

- Erstens, wir rufen eine Methode auf, um ein neues Fenster als Entität zu erzeugen

(

Windows::new). - Zweitens, wir definieren Attribute, die wir dieser Entität anfügen (

title,position,size). - Drittens, innerhalb des neu definierten Fensters erzeugen wir eine neue, hierarchisch untergeordnete Entität

(

child).

use orbtk::prelude::*;

fn main() {

// use this only if you want to run it as web application.

orbtk::initialize();

Application::new()

.window(|ctx| {

Window::new()

.title("OrbTk-Book - Chapter 1.2")

.position((100.0, 100.0))

.size(420.0, 140.0)

.child(

TextBlock::new()

.font_size(28)

.h_align("center")

.text("Hey OrbTk!")

.v_align("center")

.build(ctx)

)

.build(ctx)

})

.run();

}

- Viertens, dieses

childMethode erhält ihrerseits Argumente. Wir erzeugen eine neue Entität und beschreiben den Widget-Typ (Textblock::new). Der Textblock wird mit Attributen ergänzt (text,h_align,v_align). Das Attributtexterhält den gewünschten Zeichenwert (string). Seine Position wird über Attribute gesteuert, die für die horizontale und vertikale Ausrichtung zuständig sind (alignment). Wir wählencenterund weisen den später aufzurufenden Render-Prozess damit an, den Text innerhalb der hierarchisch übergeordneten Entität (parent) zentriert zu plazieren. In unserem Fall ist das das Fenster selbst.

use orbtk::prelude::*;

fn main() {

// use this only if you want to run it as web application.

orbtk::initialize();

Application::new()

.window(|ctx| {

Window::new()

.title("OrbTk-Book - Chapter 1.2")

.position((100.0, 100.0))

.size(420.0, 140.0)

.child(

TextBlock::new()

.font_size(28)

.h_align("center")

.text("Hey OrbTk!")

.v_align("center")

.build(ctx)

)

.build(ctx)

})

.run();

}

OrbTk versucht von sich aus, die gegebenen Anweisung zeitlich so weit

wie möglich aufzuschieben (lazy handling). Daher rufen wir die

eigentliche Methode für die Erzeugung der Struktur erst am Ende mit

(build(ctx)) auf. Die Entitäten werden instantiert. Der Renderer

wird für die veränderten Komponenten aktiv, berechnet diese neu und

gibt das Ergebnis in den Bildschirmpuffer aus.

use orbtk::prelude::*;

fn main() {

// use this only if you want to run it as web application.

orbtk::initialize();

Application::new()

.window(|ctx| {

Window::new()

.title("OrbTk-Book - Chapter 1.2")

.position((100.0, 100.0))

.size(420.0, 140.0)

.child(

TextBlock::new()

.font_size(28)

.h_align("center")

.text("Hey OrbTk!")

.v_align("center")

.build(ctx)

)

.build(ctx)

})

.run();

}

Mit der letzten Anweisung aktivieren wir die Methode, die den Event

Mechanismus kontrolliert. Die definierte Applikation wird gestartet,

die beschriebenen Widgets auf den Bildschirm ausgegeben (run).

Rust Codezeilen werden in der Regel mit einem Simikolon abgeschlossen

(;). Dies weist den Kompiler an, das eine gegebene Anweisung

abgeschlossen ist, mit der nächsten fortgefahren werden kann.

Kompilierung und ausführung sind separate Schritte

Bevor eine OrbTk Application auf der Hardware ablauffähig ist, muss

deren Quellcode über den Kompiler in Maschinencode übersetzt

werden. Ein typisches OrbTk Projekt wird ein ausführbares Programm

(binary) über das Tool cargo erzeugen. cargo legt die erstellte

Datei in den definierten Projekt-Unterordner.

In den Projekt-Metadaten der Toml-Datei können sogenannte Profile

genutze werden, die Kompiler-Optionen für die gewünschte

Ablaufumgebung einstellen (z.B. Optimierungen, Debugging).

Als Unterlassungswerte (defaults) unterstützt cargo die dev und test Profile.

Wird der Aufruf von cargo mit dem --release Argument ergänzt,

kommt das sogenannte release or bench Profil zur Anwendung.

$ cargo build --release --bin orbtk_hello.rs

$ ../target/release/hello_orbtk

Für Windows muss der backslash als Pfad-Trennung verwendet werden:

> cargo build --release --bin orbtk-hello.rs

> ..\target\release\orbtk_hello.exe

OrbTk unterstützt Entwickler mit zusätzlichen Informationen zur

Kompile-Umgebung. Hierzu kann der Kompile-Lauf um feature Argumente

ergänzt werden (derzeit: debug, log).

- debug: die Widgets werden mit Umrandungen gerendert. Dies erleichtert die Kontrolle der Einhaltung von constraints.

- log: Bei Aufruf wird beispeilsweise die Hierarchie der verwendeten Widgets visualisiert und auf der Kommandozeile ausgegeben.

$ cargo build --features debug,log --bin hello_orbtk.rs

Die Bestandteile

OrbTk stellt eine interactive functional reactive

API bereit. Es hängt dabei elementar vom Rust crate DCES ab, welches

ein Entity Component System bereitstellt. Die Interaction mit DCES wird vom

Entity Component Manager(ECM) übernommen. Einem Wrapper API, das

OrbTk widgets transparent in ECM Enititäten und OrbTk Attribute (properties) in

ECM Komponenten (components) übersetzt und verwaltet.

DCES ist wie OrbTk selbst nativ in Rust geschrieben.

The widget view

graph TD; View-->Widget-Container_1; View-->Widget-Container_2; Widget-Container_1-->Child-Widget1_1; Widget-Container_1-->Child-Widget1_2; Widget-Container_1-->Child-Widget1_n; Widget-Container_2-->Child-Widget2_1; Widget-Container_2-->Child-Widget2_2; Widget-Container_2-->Child-Widget2_n;

Workflow 1-1: Verarbeitung-Methoden Ansicht

Wenn Du eine OrbTK Anwendung erstellst kombinierst Du letztlich

widgets. Widgets sind die Kern-Bausteine von Benutzer Schnittstellen

in OrbTK. Sie sind deklarativ, d.h. sie beschreiben die Struktur von

Entitäten mit deren zugeordneten Komponenten (deren properties). Sie

werden für die Umsetzung eine bestimmen Aufgabe verwendet und sollten

alle graphischen Elemente in einem geordneten Benugtzer Interface für

die Anwendung bereitstellen (der widget-tree). Ein widget-tree wird

in einen eindeutig adressierbaren widget-container eingebunden.

In diesem Zusammenhang ist die Wiederverwendbarkeit ein wesentliche Anforderung. Bei der Implementierung eines benötigten UI-Elements ist es legitim und einfach, wenn auf bereits existierende widgets zurückgegriffen werden kann. Es ist unerheblich, wenn dies ihrerseits auf eine beliebige Anzahl von core widgets zurückgreifen.

Das derzeitige Modell ist dynamisch strukturiert und bietet die Freiheit:

- verwende eine beliebige Anzahl von vorhandenen widget Typen aus der Bibliothek

- implementiere Deinen eigenen, neue, spezialisierten widget Typ

Illustrieren wir das mit folgendem simplen Beispiel, in dem Du in

Deiner Anwendung einen FontIconBlock benötigst. Um einen solchen

widget-tree zu erzeugen kannst Du entweder ein neues Widget

MyFontIconBlock erstellen, das als Kind-Widget einen Container

verwendet, der seinerseits eine TextBox und einen Button

einbindet. Oder aber Du greifst einfach auf die Bibliotheks-Version von

FontIconBlock. zu.

Du findest den Quellcode der verfügbaren widget Bibliothek im Workspace orbtk_widgets.

Widget trait

Ein widget muss zwingend ein Widget trait erzeugen. Hierzu hilft das Makro

widget!().

Ein widget besteht zunächst aus einem Namen (z.B. Button) und

einer Liste von Eigenschaften die angebunden sind (z.B text: String,

background: Brush oder count: u32). Wird die build() Methode in

einem widget aufgerufen, wird dieses widget zusammen mit seinen

Komponenten im Entity Component System registriert. Diese

Registrierung weist ihm als Entity einen eindeutigen Index-Wert zu.

Dieser Entity werden nun die zugewiesenen Components, als

Komponenten-Namen zugeordnet und ebenfalls im ECS gespeichert.

Der widget-container stellt hierbei die erforderliche builder Struktur.

Widget Template

Jedes widget muss zwingend das Template trait implementieren. Das

template definiert neben dem Strukturaufbau auch die Standardwerte

der zugewiesenen widget Eigenschaften (seine properties).

Nehmen wir zum Beispiel einen Button, der sich aus einem Container

Widget, einem StackPanel Widget und einem TextBox Widget

zusammensetzt.

Ein ganz wesentlicher Konzeptbaustein von OrbTK ist dabei die

Trenneung eines views, also der beschreibenden Natur eines

Widget-Baums, von den Methoden die auf Benutzereingaben in der GUI

reagieren und sie verarbeiten (der Widget state). Diese Trennung ist

der Schlüssel für eine schnelle, flexible und erweiterbare Struktur

innerhalb von OrbTk.

Widget state

graph TD; State-->init; State-->update; State-->cleanup; update-->message; message-->layout; layout-->update_post_layout;

Workflow 1-2: Verarbeitungs-Methoden State

Widgets verwenden traits, die erst eine interaktive Verarbeitung

ermöglichen. Wie bezeichnen sie den Widget state. Innerhalb der

state Methoden definieren wir den Verarbeitungs- und

Kontroll-Quellcode, der an eine eindeutige Aufgabe geknüpft ist.

Es ist nicht erforderlich, einen state für ein Widget zu

definieren. Existiert kein state zu einem Widget beschneidest Du

damit aber die Möglichkeit eigenschaften während der Laufzeit

programmatisch zu verändern. Der view diese Widgets bleibt damit

statisch.

Definierst du einen Widget state, ererbt dieser neben den

implementierten Systemen auch die Werte der zugewiesenen Eigenschaften

(current values of properties). Um den programmatischen Zugriff auf

die Werte zu erhalten, muss jeder state die Default oder AsAny

traits erzeugen, bzw. ableiten (via derive macro). Du kannst für

einen state beliebige assoziierte Funktionen (methods) erzeugen,

die sowohl auf Ereignisse der zugeordneten Systeme reagieren

(z.B. messages, events) oder auch die aktuellen Werte der

Eigenschaften verändern können. Die Eigenschaften (properties) sind

im ECM gespeichert, deren Aufbau sich an der Baum Struktur orientiert

(parent, children or level entities).

Systems

Während Widgets die data structure einer OrbTk Application

definiert und organisiert, verwenden wir systems um das Verhalten

bei der Bearbeitung zu steuern.

- Layouts

- Events

- Behaviors

- Messages

Layouts

Layouts lösen das Problem, wo und wie Widgets innerhalb einer UI plaziert werden. Das erfordert die kontinuierliche Anpassung und dynamische Berechnung ihrer Größenanforderungen, verbunden mit der Plazierung des Ergebnisses zur Dastellung auf dem Ausgabegerät.

Warum brauchen wir Layouts?

Nun, betrachten wir ein eingängiges Beispiel, das in jeder modernen Applikation umgesetzt werden muss: Mehrere Sprachvarianten sind erforderlich! Und der Wechsel der gewählten Sprachvariante soll zur Laufzeit erfolgen. Wir können sicher davon ausgehen, das sich jeder verwendete Bezeichner für Felder und Beschreibungen in den jeweiligen Sprachen unterscheidet. Wortlängen und Glyphenbreiten in den Schriften sind anders. Natürlich ist ebenso die gewählte Schriftart bei der Berechnung der Größe zu berücksichtigen. Was würde passieren, wenn Du beispielsweise die Größe einer Entität statisch festlegst? Wir würden z.B. einen Button mit einer festen Größe kodieren. Wie reagierst Du nun auf Kontext-Veränderungen von untergeordneten Entitäten (childs)? Wie gehst Du damit um, dass sich z.B ein Button-Bezeichner, den der Anwender wahrscheinlich zentriert im Button Rahmen erwartet verändert?

Puh, Du als der Programmierer müsstest an alle möglichen GUI Darstellungen denken, programmatisch auf jede denkbare Spracheveränderung reagieren. Ein Alptraum! Nein, wir brauchen einen tragfähigeren Ansatz.

Unsere Lösung

OrbTk verwendet ein layout System. Dieses System unterstützen die

Möglichkeit, die Größe einer Entität anhand der natürlichen

Dimensionen des Inhalts aufzubereiten. Damit ist es im Toolkit möglich

den gesammten Entitätenbaum im Layout dynamisch anzupassen. Ändert

sich die Applikationslogik und damit die Notwendigkeit einzelne

Entitäten hinzuzufügen, zu verändern oder auszublenden wird dies für

den gesamten Baum in einem dynamischen Layout Prozess umgesetzt. Dabei

werden die individuellen Vorgaben der einzelnen Entitäten

berücksichtigt (constaints).

Die individuellen Vorgaben der Entitäten werden über Eigenschaften

(properties) als Komponenten im DCES gespeichert (components).

Das Konzept folgt einem zwei Phasen Modell. Ein Layout wird daher auch in

zwei Arbeitsschritten verarbeitet:

MeasuringPhaseArrangementPhase

Measuring

Die Measuring Phase erlaubt uns, die gewünschte Größe einer

boxed Entität zu berechnet (desired size). Die gewünschte Größe

ist eine Struktur, die die maximalen Werte für Breite und Höhe einer

Entität angibt. Diese Werte werden innerhalb des DCES persistent

gespeichert. Wenn die Verarbeitung eine Wertänderung der gewünschten

Größe feststellt (die gespeicherte und die aktuelle Größe

unterscheiden sich), wird die Kennzeichnung dirty in der Struktur aktualisiert.

Arrangement

Die Plazierung (Arranging) erfolgt in einem weiteren separaten

Schritt. Der Vorgang arbeitet den Baum der angesprochenen Elemente in

einer Schleife ab. Dabei verwendet er die bounds es jeweiligen

Elements. Ein bound beschreibt die finalisierte Position der

Ausrichtung des Elements (Höhe, Breite) und speichert diese im DECS.

Ein Verarbeitungs-Prozess wird nur dann initiiert, wenn ein Element

innerhalb des Baums eine neue Anordnung erzwingt. Alle Elemente werden

nur dann mit den neuen Positionen im Ausgabe-Puffer (render buffer) neu

angeordnet, wenn ihr aktiver Status die als dirty gekennzeichnet ist.

Layout Methods

OrbTk unterstützt unterschiedliche Layout Methoden. Dies sind darauf

optimiert, spezifische Anforderungen der unterschiedlichen

Widget-Typen zu berücksichtigen:

- Absolute

- Fixed size

- Grid

- Padding

- Popup

- Stack

Du findest deren Quellcode im Workspace orbtk_core im Unterverzeichnis layout.

Weitere Informationen zu diesen Methoden werden im

Kapitel: Orbtk Core besprochen.

Events

- bottom-up

Ein Ereignis wandert bei der Verarbeitung vom Auftreten am Blatt des

Enitätenbaums (leaf entity) zum Stamm (root entity). Also von

Unten nach Oben - oder von Aussen nach Innen.

- top-down

Ein Ereignis wandert bei der Verarbeitung vom Auftreten am Stamm

(root entity) zu den Blätter des Enitätenbaums (leaf entity). Also

von Oben nach Unten - oder von Innen nach Außen.

Behaviours

Es existieren diffenzierte Methoden für die Bearbeitung logisch gruppierter Ereignisse. Hierzu zählen derzeit die Ereignis-Klassen

- Mouse Behaviors

- Selection Behaviors

- Text Behaviors

Die Ereignisse können sowohl von Eingabe-Geräten (z.B. Tastatur, Maus) aber auch aus der funktionalen Logik heraus erzeugt werden (z.B. durch Fokus Änderung, Textanpassungen, etc.)

Messages

Über das Konzept von MessageAdaptern können Nachrichten zwischen beliebigen

Sender- und Empfänger-Widget gesendet und ausgelesen werden. Die

verwendeten Methoden sind thread save.

Jedes Widget kann im State code eine message Methode

definieren. Hier ist der Entwickler frei, welche MessageAdapter

berücksichtigt werden sollen. Die Verarbeitungslogik für ausgelesende

Nachrichten ist somit wahlfrei.

Framework Elements

Alle Elemente des ObtTk Frameworks sind als Sub-Module innerhalb des API organisiert.

Die OrbTk Workspace Struktur

Der Entwicklungsprozess von OrbTk berücksichtigt folgende definierten Basis-Prinzipien:

- Modularität

- Erweiterbarkeit

- Nativen Multiplattform Support

- Minimieurng von Abhängigkeiten

Innerhalb des Rust Ecosystems existiert die Funktionalität von

workspaces. Sie sind hilfreiches Instument, ein anwachsendes crate

in sinnvolle kleinere logische Code-Einheiten aufzubrechen. Neben dem

Ordnungsfaktor helfen workspaces ebenso sich wiederholende zu

reduzieren. Dies gelingt dadurch, dass nur veränderten Code-Blöcken

neu übersetzt werden müssen.

Es ist daher nachvollziehbar, das OrbTk sich dieser Sturktur bedient.

Das Toolkit ist in folgende workspaces unterteilt:

- orbtk

- orbtk_core

- orbtk_orbclient

- orbtk_tinyskia

- orbtk_widgets

- proc_macros

- utils

Diese Komponenten und ihre Relationen zueinander im Toolkit werden in den folgenden Kapiteln Schritt für Schritt erläutert.

Workspace OrbTk

This workspace is the entry point into the framework code. If you are familiar with Rust code, we are following best practice.

Lets have a quick look at the src sub-directory. As usual you will

find a lib.rs source file.

Obviously here the code starts to define the crates type “lib”. The

next lines define an outer documentation block, which serves as a

short introduction. Outer documentation lines are encoded with two

slashes followed by an exclamation mark (//!).

A very strong feature of the Rust toolchain is the availability of an

inline documentation subsystem. We do use this feature extensively

within OrbTk, to document every public accessible code module,

public functions, structure or enumeration. Inner documentation blocks conventionally start with three slashes (///).

To render the documentation lines, a simple

cargo doc

will generate the online documentation, corresponding to the downloaded release version. We will timely upload negotiated versions to Docs.rs.

Back to our structure. To keep the code tight and clear, Rust supports the concept of modules. Like in most other higher programming languages this allows to subdivide your code into related, condense function blocks. This resolves to increased clarity and readability. To put the needed modules or crates into scope, take advantage of the use statement.

Both principles helps quite a bit to keep a lean structure beside a

nice developer experience. Ease of use is one main goal, so we

prepare prelude modules, that will take care to present the most

needed peaces accessible in your code. Using short and pregnant

descriptors should be enough to consume the offered OrbTk modules

and functions in your code.

Workspace orbtk_core

Application

The application crate provides the base api inside an OrbTk application.

Its elements are consumed via dedicated modules organized in the other sub-crates.

The ContextProvider

This structure is a temporary solution to share dependencies inside an

OrbTk application. Right now, if the app is started, a new

ContextProvider object is created. The interconnection between

sender and receiver are handled using asynchronous channels with

sender/receiver halves (mpsc).

-

window_sender A

WindowRequestis used to send the given request to the named window. -

shell_sender A

ShellRequestis used to send the given request to the application shell. The application shell is aware of the handled windows. They are differenciated via individualWindowAdapterobjects.

In the given version this module isn’t thread save. It will be refactored in the next upcoming release.

The WindowAdapter

Each WindowAdapter handles its unique tree, event pipiline and

shell. They are dynamically stored in the undelying DCES via ECM

methods.

The shell will react on UI events. The code for dedicated events are organized in explicit modules that will trigger their handlers:

- activation events

- clipboard updates

- drop events

- focus events

- key events

- mouse events

- text input events

- window resize events

- window scroll events

- window system events (like

quit)

The EventAdapter provides a thread safe way to push events to the

widget tree of a window.

The Overlay widget

The Overlay widget allows the handling of children at the top of the

tree. Thus its children will be presented on top of all other widgets

grouped in the widget-tree.

Layout

A layout is used to dynamically order the children of a

widget. Before we can arrange the components on screen, their sizes,

bounds and constraints have to be measured. The ordering process

will result in a parent / child relation (tree), that is represented

and handled in the ECM. In a next step, the tree components are

arranged. The result is rendered into an output buffer

(view). Last not least the updated areas are signaled to the output

screen.

Note: New rendering of a widget will only occur, if any of its child

entities is marked dirty.

To measure components, the code will provide suitable defaults for

each property as well as a desired_size. The desired_size will

resolve the height and width property of the child element.

This values can either be overwritten with an explicit component

property inside rusts view-code of your app, or while referencing to

definitions using a style property. Please take into account, that

a given style definition will take precedence over all explicitly

defined property elements inside the code. OrbTk will not respect a

mixture of both declarations.

New rendering of the child will only occur, if any of its properties is

marked dirty.

The absolute placement

Only components with a visibility property that is labeled with a

Collapsed or Visible option will be taken into account, when

calculating bounds and constraints of a child. The resulting bounds are

points, with absolute x and y positions on the screen (floating point values).

The fixed size

A fixed sized layout is defined by fixed bounds for its child. Think of images that have to be rendered with a given size, or a minimum size of a text box.

Grid layout

The grid layout is a specialized case of the default alignment layout. If you declare rows and columns, the child blocks are calculated suming up each individual block bounds inside the corresponding row or column.

You may stretch the blocks to the choosen dimension (horizontal vs. vertical). As a result, if you resize the window of the running app, that grid element will consume the extra size available because of your interactive change. Vice versa, the elements will shrink down until the grid child will reach the defined minimum bound.

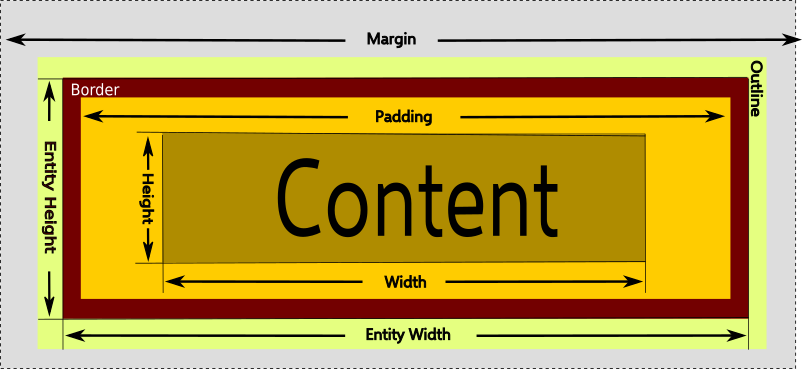

Padding layout

Padding may be needed, as a property of a broad range of

components. The measurement cycle will calculate the padding value (a

floating point value) as a constraint that is added to the space

requirements of the associated content component. You may think of the

padding as a surrounding with a given thickness, that is placed

arround your content.

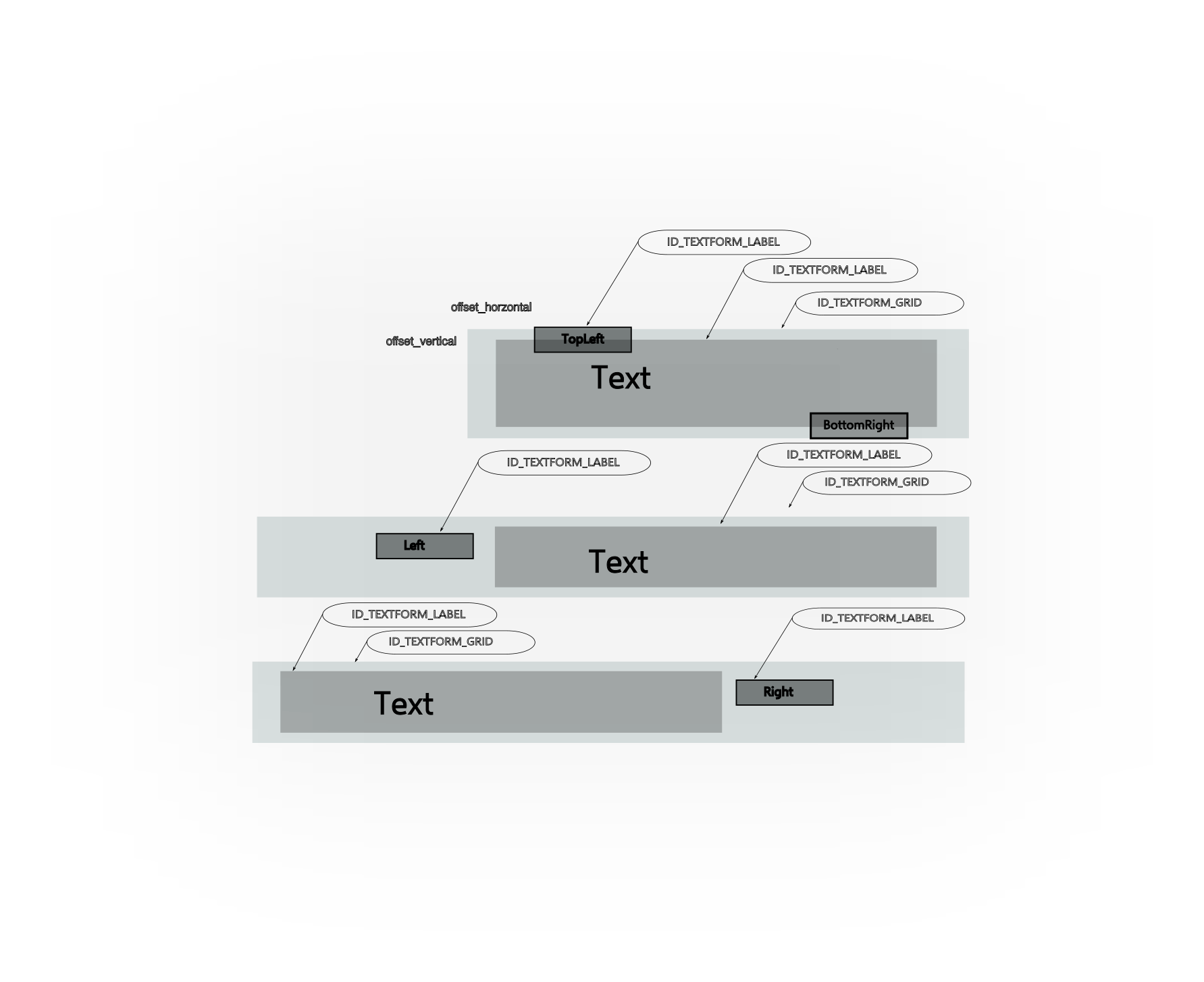

The following image visualizes the dependencies.

Image 2-2: Layout constraints

Popup layout

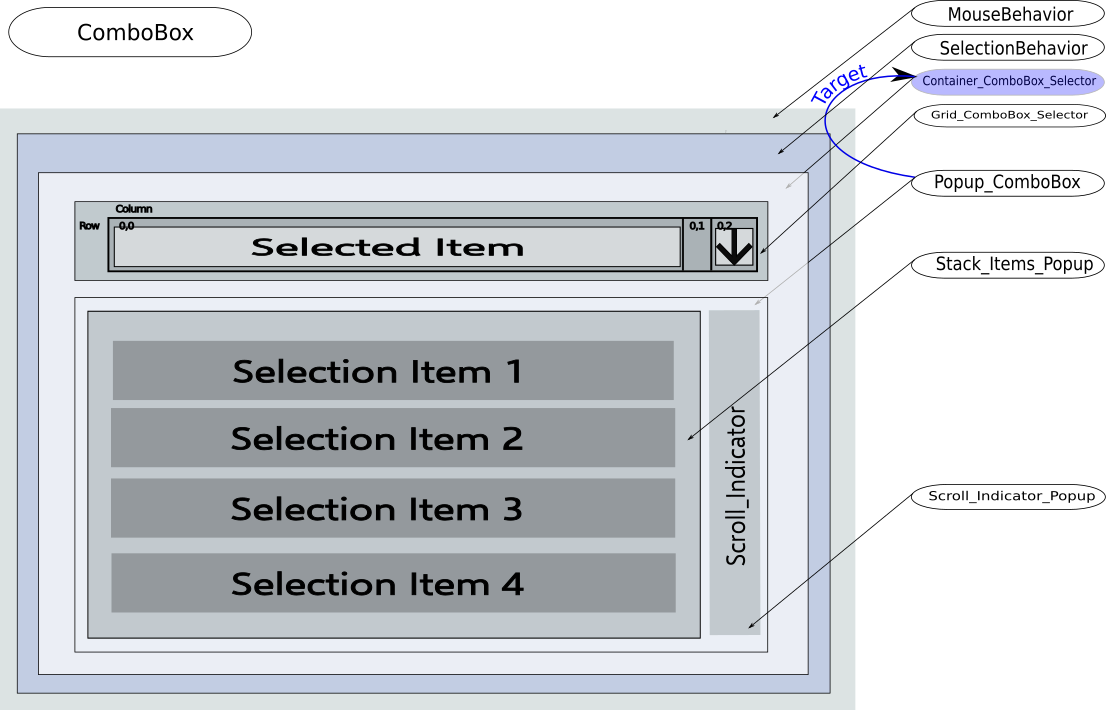

The popup layout is a specialized case of the default alignment layout. A popup is typically needed to render content, that is related to a given target widget. That includes the position of the popup itself, as well as its dynamic created content.

You can find a common use case of a popup if you study the OrbTk code

of a list box. The list box elements are collected in a stack

widget. The stack itself is placed in a popup widget. And the

popup widget is placed right below the text block that offers a

drop-down selection arrow.

Stack layout

The stack layout is a specialized case of the default alignment

layout. A stack offers a use case, where you want to place other

widgets in a congruent horizontal or vertical order. You may

define a spacing property. This given floating point value is used

as a seperator between each stack member.

Localization

Localization is a research task by itself, if you want to resolve all syntactic rules that are found when writing prose in different languages. OrbTk’s localization crate isn’t ready to resolve all this complexity, but this may improve in further releases.

Starting with the given implementation, localization can offer methods, that

are able to match and replace text strings. The usage of the localization crate is

optional. If you don’t need any multi lingual adaptions inside your widgets, simply

do not include the localization sugar.

The building blocks of localization

If you want to enable the users to select and change the desired display language of the GUI at runtime, the toolkit needs to match up a requested text strings (the key) that should be presented inside the view and substitute it with the corresponding translation string (the target value). Dictionaries are used to organize the keys as word lists.

OrbTk’s localization implementation has choosen to persitently store

the translation strings inside a RON file. When introducing

the new syntax structure used inside a RON filetype, it was one goal

of the authors to easily match rust types to ron types. That is

exactly the development goal from the RON authors:

“RON is a simple readable data serialization format that looks similar to Rust syntax. It’s designed to support all of Serde’s data model, so structs, enums, tuples, arrays, generic maps, and primitive values.”

You can save each supported language in its individual ron file. The language

files need to be distinctable. A natural way to implement this requirement

is the usage of unique language ids. Most *operating systems take advantage

of a locale subsystem, and save the identification of the active language in

the lang enviroment variable. It’s good practice to include the language id in

the corresponding ron file name.

When you include the localization functionality in your OrbTk code, you

should define constants for each supported language id, that will reference the

ron file in question.

When calling the RonLocalization methods addressing the combination of a language

id and the corresponding dictionary you are able to store the result in language

variable. The crate methods will handle all the heavy lifting to substitute the

source values of the text attributes inside the views with their matching translation

strings in the addressed dictionary.

The ron file structure

In OrbTk, the structure RonLocalizationBuilder is defined to take values for

the following parameters

- language: a String

- dictionaries: a HashMap

The ron filename representing a language localization should include the language identifier to ease its distiction from another.

Dictionaries itself are stored The dictionary is represended by a key value pair

A class Dictionary will include a map named words.

The ron type map is like a type struct, but keys are also values instead of

just beenig identifiers.

- using a ron file

Activation of the localization crate inside your source code boils

down to this short example code.

Filename: localization.rs

static LOCALIZATION_ES_ES: &str = include_str!("../assets/localization/dictionary_es_ES.ron");

We do define two language identifiers:

- _de_de: referencing a ron file with german translation strings

- _es_es: referencing a ron file with spanish translation strings

Application::new()

.localization(es_es)

When creating the Application block, we do pipe in the localization property. To keep this example simple, a hardcoded de_DE is choosen. The showcase example inside the orbtk source code implements a tab widget, that offers a dropdown list, to dynamically change the active language variant.

let es_es = RonLocalization::create()

.language("es_ES")

.dictionary("es_ES", LOCALIZATION_ES_ES)

.build();

/* disabled german translation file

* let _de_de = RonLocalization::create()

* .language("de_DE")

* .dictionary("de_DE", LOCALIZATION_DE_DE)

* .build();

*/

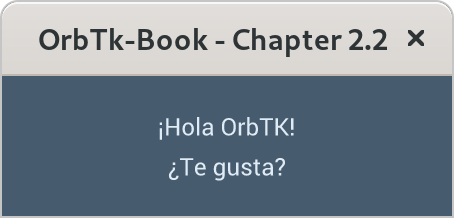

To compile this example code, go ahead and enter the following comand in your terminal window:

$ cargo run --release orbtk_localization

Your screen should present an application window showing the translated spanish strings.

Image 2-2: Application window with spanish localization strings

Sure, this code isn’t elegant nor will it suite the real application

demands. What it does show is the logic, to bind a ron file (storing

the translations of a given language) to a const. When calling

RonLocalization, the text method will resolve text attributes

inside a view or any rust primitive with the translation text resolved

in the language dictionary.

Properties

Every entity that is managed via the provided ECM methods (in most cases this will

be widgets) will have associated components. If we are

talking about components inside the toolkit, we name them properties

of a given object.

Layout

Our aim is a dynamic ordering of objects inside the render buffer. This ordering needs to respect the specific properties of each object making up the object tree. All properties declared for the addressed objects will sum up the constraints that need to be respected within their layout.

Logical units of properties ease the measurement and assignment process of the given object tree.

Blocks

Inside OrbTk the BlockBuilder method handles a block. A block is a

term that defines an object inside the render surface. A legacy form of

the API was using the idiom row or column to define the position

of a block inside a grid widget. We moved on to use blocks as a

generic term that can be used in all widgets. Blocks will inherit

default properties:

- a block size

- its minumum size

- its maximum size

- its current size

If we measure a block size, we can choose from an enumeration of valid expressions:

- Auto: The largest child will be used to measure the block size.

- Stretch: The block will be expanded and consume all of the available size.

- Size: An explicit floading point value.

ScrollViewerMode

To describe the vertical and horizontal scroll behavior of a widget,

we do make use of the ScrollViewerMode. The ScrollViewerMode will

evaluate a valid enumeration value of the ScrollMode. Per default it

will automatically assign the Auto value. That will take care

that the layout logic is able to automatically adjust and manage scroll

movements of associated widget elements (e.g. in ListViews, SelectionViews or TextBoxes).

You may want to handle this scroll movements via your own dedicated

code. Just adapt the mode property horizontal and vertical to your needs and select

ScrollMode::Custom. To completely disable any scrolling logic select

ScrollMode::Disabled.

Widget

FocusState

To offer natural interactivity with the implemented UI, we should

respect workflow standards. E.g a user is expecting the cursor and the

possibility to change a widget element at the next logical

position. Imagine a form, where the UI offers a layout to enter some

address fields. When you activate such a form, you do expect the

cursor position on the first element of the form. Thus, we need the

concept of a Focus that enable the state logic to preset UI

interaction onto a specified element. The FocusState offers methods

to control the state information of widget elements:

- Request the focus for an entity.

- Remove the focus from an entity.

- Reference the current focused entity.

- Check the focus state of an entity.

KeyboardState

The keyboard state tracks which keys are currently pressed. The active state is stored in a lazy-loaded HashMap.

Beside common key activities, you may need to react on generic

modifier keys (Alt, Ctrl, Hyper, Shift). Helper functions

offer several convenience methods to handle such keyboard events. A

generic method comes in handy, if you don’t care which modifier key is

down (Shift-left or Shift-right => Shift). The example section

will also tackle the case, where a combined event (Ctrl+S) keyboard

state is handled.

Render Objects

Services

System

Theming

Tree

The Widget base

Workspace orbtk_client

WIP: The OrbTk GUI client modules

Workspace orbtk_tinyskia

Rendering is a key component of the toolkit. Everybody is expecting state of the art presentation of implemented widgets. User interaction that will result in layout and entity changes inside the GUI should be updated as soon as possible. A comfortable user experience is mainly influenced by fast rendering tasks. New rendering of layouts should only take place, if constraint changes will need to do so. Entities and their attributes will only require new rendering if a user interaction changes their state to be dirty.

Lets summarize the main goals of OrbTk rendering infrastructure:

-

API encapsulated access to all renderer functions

This design decision is taken to keep freedom for further development of OrbTk when it comes to support different renderers. We are able to support

- different versions of a given renderer

- support different renderer for different target platforms

-

2D rendering

We need a fast and complete implementation of all rendering functions that are supported in the OrbTk toolkit. The following summary is a list of

tiny-skiaprovided functions:- Pixmaps

- Canvas

- Path

- geometry primitives

- Blending modes

- Path filling

- Anti-aliased Path filling

- Path stroking

- Path hairline stroking

- Anti-aliased Path hairline stroking

- Stroke dashing

- Gradients (linear and radial)

- Pixmaps blending (image on image rendering)

- Patterns

- Fill rect

- Stroke rect

- Rectangular clipping

- Clipping

- Anti-aliased clipping

- Analytical anti-aliased Path filling

- Dithering

- Blending modes

We are looking forward to a Rust native ecosystem that handles text rendering. This is a complex task and by the time of writing a

complete library addressing this issue isn’t available.

The Rust community has developed building blocks, like

- a Font parser: ttf-parser.

- a Text shaper: rustybuzz or all-sorts.

- a Font database: fontdb (supporting a font fallback mechanism).

The missing peace, beside the glue code to use the components inside

orbtk_tinyskia is a high-quality glyph rasterization library. Preferably it will offer a FreeType level of

quality. ab_glyph_rasterizer or fontdue might evolve to fill this

gap.

Workspace orbtk_widgets

As a UI developer consuming OrbTk, you most probably will get in

touch with the widget sub-crate. If you get comfortable with the

terminology of views and their states, it’s quite easy to

implement even complex structures. The GUI components are declarative

and you will code them inside the view blocks. All callbacks that

will handle the functional processing are coded inside the state

blocks. User input (e.g. mouse events, keyboard input) as well as

event handler generated feedback is handled and processed from methods

of the associated state blocks.

The behavior modules are separated to handle specialized cases. If

an event is emitted that belongs to a behavior class, the associated

action is handled by a behavior method. In particular you will

recognize modules for the following behaviors:

- focus

- mouse

- selection

- text

Views

When you create a view block inside an OrbTk application, it is

required to insert definitions that declare what elements are going to

be present inside the user interface.

What is a View

If you take the Rust code that makes a view in a structural way, it

will answer to the following questions:

- Which entities are used?

- What is the entities tree formed?

- What attributes are coupled with the given entity?

- What handlers should take care when a given event is emitted?

What is the code structure of a View

First, the inside the source code that takes your view needs to call

the widget! macro. This macro automatically implements the Widget

trait. When instantiated, it will inherit all default properties from

a base widget, which gets you started with consistent preset values.

The syntax of this macro call will require you to select

- the desired

view-name(e.g: “NavigationView”) - optional: the name of the associated

state-structure(e.g: “”)

If you like to assign property names inside the view, go ahead and introduce an extensible list of the property-variables. Each variable will take a name and define its associated type.

In a next step you enhance the Template trait with an implementation

of your new widget. You are required to code a function called

template. The syntax of this function will take the following

arguments

self, the implementation of your view-name- the

Idof the entity - the

Context, as a mutual reference to the BuildContext

All the widget structures you are going to use inside of template

will be coded as child’s of self.

States

When you create a state block inside an OrbTk application, it is

required to define the structures you want to work on in the State

implementation.

What is a State

The Rust code that makes a state is associated to the view block

of your widget. Go and ask yourself:

- What actions should be processed on a given event?

- How should we handle user input?

- What happens if an entity attribute is changed and gets dirty?

From a procedural point of view, states will provide methods that are processed depending of the event status inside the a widget.

graph TD; State-->init; State-->update; State-->cleanup; update-->message; message-->layout; layout-->update_post_layout;

Workflow 1-1: State handling methods

What is the structure of a State

First, inside the source code that takes your state, you will go and

declare its structure name. This name corresponds to the parameter

value you chose inside the widget! macro call of your widgets

view (e.g “NavigationState”).

In a next step you enhance the State trait with an implementation of

your state structure. Most probable, you create and adapt the

following functions:

The cleanup function

This function is called as a destructor, when a widget is removed or your application terminates.

The init function

This function is called to initialize the widget state. You can preset attributes before the view is activated and presented to the user.

The message function

The message subsystem is offering methods to chain events, that can

be interchanged and accessed from any defined state. You will code a

message function to take advantage of this functionality.

The syntax of this function will take the following arguments

self, the implementation of your message function- the mutable

messagesvariable, referencing the MessageReader - the

Context, as a mutual reference to the BuildContext

As already explained, you should define an action enumeration, (e.g

“NavigationAction”), that will code the values that are possible or

desired (e.g “SaveSettings”, “LoadSettings”). Inside the message

function you will loop through the messages and match the action

values you are interested in.

The update function

Whenever the attribute of an entity is changed, OrbTk will render it

dirty. The update function is taking care to react on any triggered

dirty state. You will probably define an Action enumeration that

will name and list all action states you are interested in. Now, if

you match an action in the update function, you can react on this

with all the Rust syntax flexibility.

The update_post_layout function

OrbTk will run this function after the rendering crate has processed the new layout for your view.

Workspace proc_macros

WIP: Precedural macros

Workspace utilities

WIP: OrbTk helper utilities

OrbTk Widget Templates

Within this sub-section we are going to collect and discuss the

structure of officially provided OrbTk widget Templates. We hope to

cover interesting aspects.

For each template type we do provide a simple reference application,

that will show the features and functionality offered by the

illustrated code. Take the in-lined comments and anchors as a tutorial

on how to take advantage of the presented logic while including the

widget inside your own OrbTk code. If we did well, you can

concentrate on the parts we like to emphasize.

Inside the library, the collection of the annotated example code is filed in

the sub-directory listings.

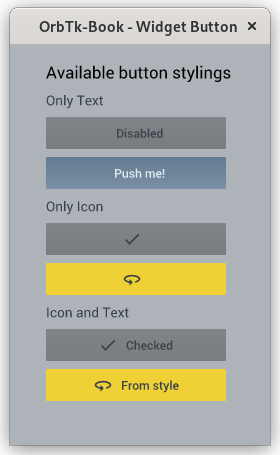

Template: Button

This subsection will describe an OrbTk UI element called Button.

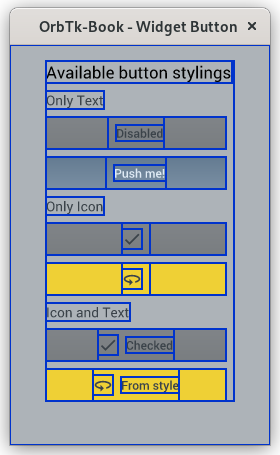

The complete source that demonstrates this template element is presented in Listing 3-1. After a successful compile run, it should produce the attached screen-shot:

We did compile for a desktop target (Linux). And if you did clone the book source to your development system, the corresponding source-code examples can be found inside the listings sub-directory. To compile it yourself, first change into this directory

src/listings/ch03-01-widget-button/listing-03-01

Next, use cargo to pipeline the compile and linking process. In the end the target binary will be executed. If you like to get a rendered output, that annotates the tree structure with respect to their bounds, please make use of the feature debug. This feature will draw blue boxes around any involved entities.

$ cargo run --features debug

Recap and annotation

The anatomy of this template

Let’s review the relevant parts of the widget_button application.

OrbTk code framing the app

As a first step, We put the needed OrbTk parts into scope.

use orbtk::{

prelude::*,

widgets::themes::theme_orbtk::{

{colors, material_icons_font},

theme_default_dark,

},

};

Next we do declare "str" constants to any involved id’s. This isn’t

strictly necessary, but helps to identify the entities by meaningful names.

pub static ID_BUTTON_CONTAINER: &str = "ButtonContainer";

pub static ID_BUTTON_CHECK: &str = "ButtonCheck";

pub static ID_BUTTON_TEXT_BLOCK_HEADER: &str = "ButtonTextBlock Header";

pub static ID_BUTTON_TEXT_BLOCK_1: &str = "ButtonTextBlock 1";

pub static ID_BUTTON_TEXT_BLOCK_2: &str = "ButtonTextBlock 2";

pub static ID_BUTTON_TEXT_BLOCK_3: &str = "ButtonTextBlock 3";

pub static ID_BUTTON_ICONONLY: &str = "ButtonIcononly";

pub static ID_BUTTON_TEXTONLY: &str = "ButtonTextonly";

pub static ID_BUTTON_UNCHECK: &str = "ButtonUncheck";

pub static ID_BUTTON_STACK: &str = "ButtonStack";

pub static ID_BUTTON_STYLED: &str = "ButtonStyled";

pub static ID_BUTTON_VIEW: &str = "ButtonView";

pub static ID_WINDOW: &str = "button_Window";

The main function instantiates a new application, that makes use of the theme_default_dark and a re-sizable Window as its first children. For a deeper insight into this UI elements, please consult the relevant part in this book.

We will now focus our interest on the next part, where we do create a ButtonView as a child inside the Window entity.

.child(

ButtonView::new()

.id(ID_BUTTON_VIEW)

.name(ID_BUTTON_VIEW)

.min_width(120.0)

.build(ctx),

)

The syntax advises the compiler, to implement a ButtonView for the

Template trait. The widget!() macro relieves us to type out all

the boiler plate stuff and takes care to create the needed code sugar.

// Represents a button widgets.

widget!(ButtonView {});

We do use a Container widget as a first child inside the template method. It allows us, to place a padding around the included children. Please refer to its documentation section for a deeper dive.

.child(

Container::new()

.id(ID_BUTTON_CONTAINER)

.name(ID_BUTTON_CONTAINER)

.background(colors::BOMBAY_COLOR)

.border_brush(colors::BOMBAY_COLOR)

.border_width(2)

// padding definition:

// as touple clockwise (left, top, right, bottom)

.padding((36, 16, 36, 16))

.min_width(140.0)

The container will have a Stack child, that we do consume to attach multiple children in a horizontal direction. TextBlocks are used to render some header text above the Button children. This is the part of the code, that we are finally interested in.

OrbTk widget specific: Button

We are going to consume a button widget.

As any other template inside the widget tree of OrbTk, the template

is rendered with a preset of sane property values. If you choose not to

explicitly declare any property values inside the view code, the

defaults coded in the template definition will be evaluated.

The following Class-Diagram presents the button internal widget tree, including its default property values:

classDiagram

Button --o MouseBehavior

MouseBehavior --o Container

Container --o Stack

Stack --o FontIconBlock

Stack --o TextBlock

Button : name["button"]

Button : style["button"]

Button : height[36.0]

Button : min_width[64.0]

Button : background[colors-LYNCH_COLOR]

Button : border_radius[4.0]

Button : border_width[0.0]

Button : border_brush["transparent"]

Button : padding['16.0, 0.0, 16.0, 0.0']

Button : foreground[colors-LINK_WATER_COLOR]

Button : text[]

Button : font_size[orbtk_fonts-FONT_SIZE_12]

Button : font["Roboto-Regular"]

Button : icon[]

Button : icon_font["MaterialIcons-Regular"]

Button : icon_size[orbtk_fonts-ICON_FONT_SIZE_12]

Button : icon_brush[colors-LINK_WATER_COLOR]

Button : pressed[false]

Button : spacing[8.0]

Button : container_margin[0]

MouseBehavior : pressed(id)

MouseBehavior : enabled(id)

MouseBehavior : target(id.0)

Container : background(id)

Container : border_radius(id)

Container : border_width(id)

Container : border_brush(id)

Container : padding(id)

Container : opacity(id)

Container : margin("container_margin", id)

Stack : orientation(horizontal)

Stack : spacing(id)

Stack : h_align(center)

FontIconBlock : icon(id)

FontIconBlock : icon_brush(id)

FontIconBlock : icon_font(id)

FontIconBlock : icon_size(id)

FontIconBlock : v_align("center")

TextBlock : font(id)

TextBlock : font_size(id)

TextBlock : foreground(id)

TextBlock : opacity(id)

TextBlock : text(id)

TextBlock : v_align("center")

Workflow 3-1: Button tree

The first button child hasn’t choosen an icon. Thus the rendered output will just present the text property.

.child(

Button::new()

.id(ID_BUTTON_TEXTONLY)

.name(ID_BUTTON_TEXTONLY)

.enabled(false)

.max_width(180.0)

.min_width(90.0)

.text("Disabled")

.build(ctx),

)

The button hasn’t declared a “text” property. Thus the rendered output will just present the icon content.

.child(

Button::new()

.id(ID_BUTTON_CHECK)

.name(ID_BUTTON_CHECK)

.enabled(false)

.icon(material_icons_font::MD_CHECK)

.max_width(180.0)

.min_width(90.0)

.on_enter(|_, _| {

println!("Enter Button boundries");

})

.on_leave(|_, _| {

println!("Leave Button boundries");

})

.build(ctx),

)

Using a style method. Properties assingned via a theme definition take precedence over property definitons inside the view code.

.child(

Button::new()

.id(ID_BUTTON_STYLED)

.name(ID_BUTTON_STYLED)

.style("button_primary")

.icon(material_icons_font::MD_360)

.max_width(180.0)

.min_width(90.0)

.pressed(true)

.text("From style")

.build(ctx),

)

.build(ctx),

Complete example source

Find attached the complete source code for our orbtk_widget_button example.

//!

//! OrbTk-Book: Annotated widget listing

//!

use orbtk::{

prelude::*,

widgets::themes::theme_orbtk::{

{colors, material_icons_font},

theme_default_dark,

},

};

pub static ID_BUTTON_CONTAINER: &str = "ButtonContainer";

pub static ID_BUTTON_CHECK: &str = "ButtonCheck";

pub static ID_BUTTON_TEXT_BLOCK_HEADER: &str = "ButtonTextBlock Header";

pub static ID_BUTTON_TEXT_BLOCK_1: &str = "ButtonTextBlock 1";

pub static ID_BUTTON_TEXT_BLOCK_2: &str = "ButtonTextBlock 2";

pub static ID_BUTTON_TEXT_BLOCK_3: &str = "ButtonTextBlock 3";

pub static ID_BUTTON_ICONONLY: &str = "ButtonIcononly";

pub static ID_BUTTON_TEXTONLY: &str = "ButtonTextonly";

pub static ID_BUTTON_UNCHECK: &str = "ButtonUncheck";

pub static ID_BUTTON_STACK: &str = "ButtonStack";

pub static ID_BUTTON_STYLED: &str = "ButtonStyled";

pub static ID_BUTTON_VIEW: &str = "ButtonView";

pub static ID_WINDOW: &str = "button_Window";

fn main() {

// Asure correct initialization, if compiling as a web application

orbtk::initialize();

Application::new()

.theme(

theme_default_dark()

)

.window(|ctx| {

Window::new()

.id(ID_WINDOW)

.name(ID_WINDOW)

.title("OrbTk-Book - Widget Button")

.position((100.0, 100.0))

.size(260.0, 400.0)

.resizable(true)

.child(

ButtonView::new()

.id(ID_BUTTON_VIEW)

.name(ID_BUTTON_VIEW)

.min_width(120.0)

.build(ctx),

)

.build(ctx)

})

.run()

}

// Represents a button widgets.

widget!(ButtonView {});

impl Template for ButtonView {

fn template(self, _id: Entity, ctx: &mut BuildContext) -> Self {

self.id(ID_BUTTON_VIEW)

.name(ID_BUTTON_VIEW)

.child(

Container::new()

.id(ID_BUTTON_CONTAINER)

.name(ID_BUTTON_CONTAINER)

.background(colors::BOMBAY_COLOR)

.border_brush(colors::BOMBAY_COLOR)

.border_width(2)

// padding definition:

// as touple clockwise (left, top, right, bottom)

.padding((36, 16, 36, 16))

.min_width(140.0)

.child(

Stack::new()

.id(ID_BUTTON_STACK)

.name(ID_BUTTON_STACK)

.spacing(8)

.child(

TextBlock::new()

.id(ID_BUTTON_TEXT_BLOCK_HEADER)

.name(ID_BUTTON_TEXT_BLOCK_HEADER)

.font_size(18)

// generic color names:

// constants from crate `utils` -> colors.txt

.foreground("black")

.text("Available button stylings")

.build(ctx),

)

.child(

TextBlock::new()

.id(ID_BUTTON_TEXT_BLOCK_1)

.name(ID_BUTTON_TEXT_BLOCK_1)

.font_size(14)

// generic color name : rgb value

.foreground("#3b434a")

.text("Only Text")

.build(ctx),

)

.child(

Button::new()

.id(ID_BUTTON_TEXTONLY)

.name(ID_BUTTON_TEXTONLY)

.enabled(false)

.max_width(180.0)

.min_width(90.0)

.text("Disabled")

.build(ctx),

)